The credit ratings of emerging markets are experiencing a positive improvement

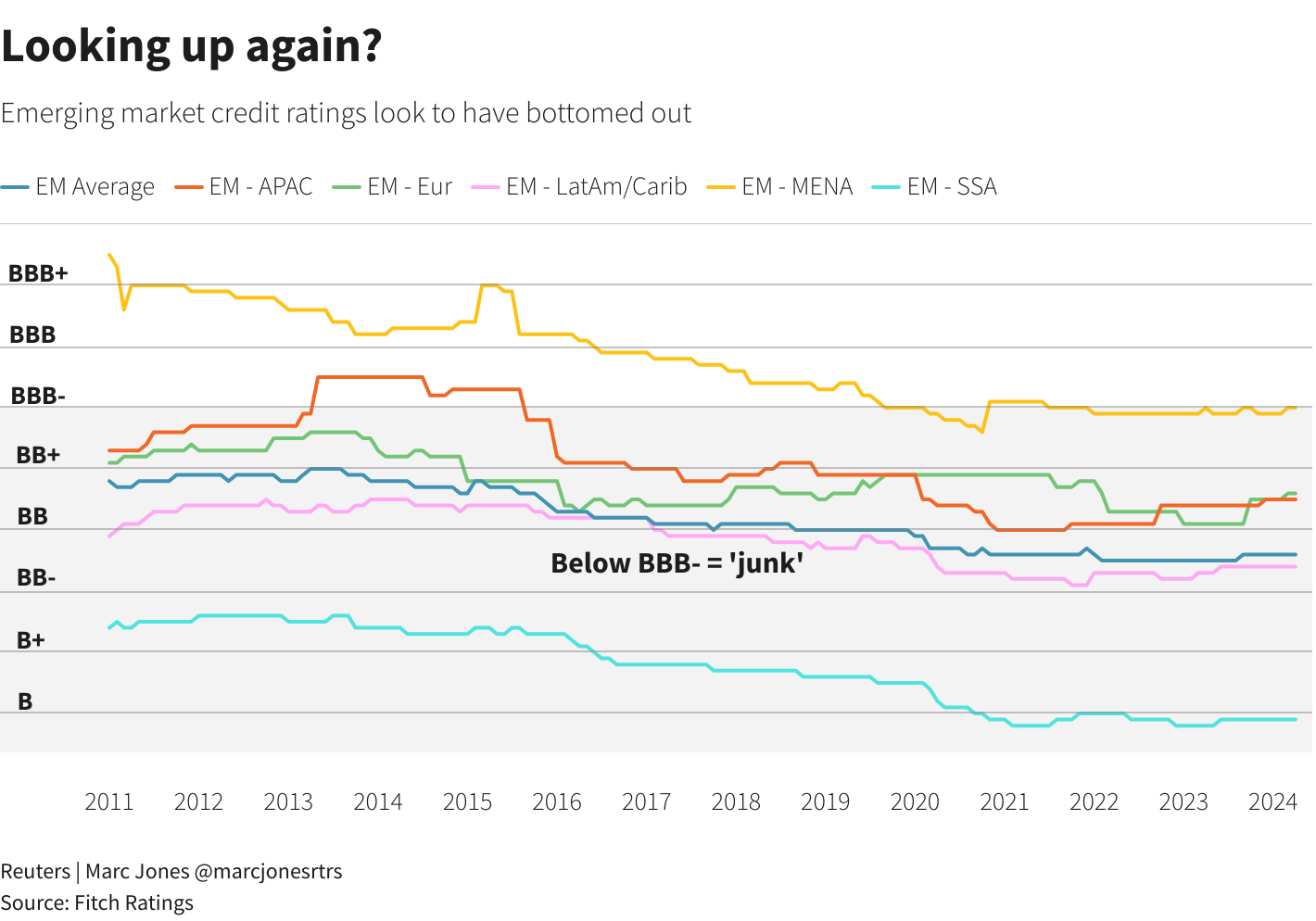

There is increasing evidence that the decline in sovereign credit ratings, which has been ongoing for a decade, is now beginning to reverse. This trend is observed not only in countries like Brazil, Nigeria, and Turkey, but also in riskier emerging markets such as Egypt and Zambia.

Economists often monitor ratings as they have a significant impact on a nation’s borrowing expenses. Currently, many economists are drawing attention to a surprising reversal that contradicts the typical concerns regarding increasing debt burdens.

Bank of America reports that about 75% of the changes in sovereign ratings made by S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch this year have been favorable, in contrast to the nearly 100% negative changes observed during the first year of the COVID pandemic.

Now that the previous events, including the jump in global interest rates, are behind us, we can expect more positive developments in the future.

Moody’s currently has 15 emerging economies under a positive outlook, which means they are being closely monitored for a potential upgrade. This is one of the largest numbers of developing economies being watched for an upgrade that Moody’s has ever had. S&P has a rating of 17, while Fitch has achieved its highest ratio of positive to negative outlooks since the ratings rebounded after the global financial crisis in 2011.

According to Fitch’s global head of sovereign research, Ed Parker, the improvement can be attributed to a variety of factors.

Certain countries have experienced a widespread economic rebound from the effects of COVID-19 and the energy price surges resulting from the conflict in Ukraine. According to him, certain countries are experiencing positive changes in their policymaking, specifically tailored to their own country. Additionally, a select set of nations with low credit ratings, known as “frontier” nations, are now able to once again access debt markets, which is proving advantageous for them.

Aaron Grehan, the head of EM hard currency debt at Aviva Investors, characterizes the recent surge of upgrades as a “decisive change” that has also corresponded with a significant decrease in the interest rates that emerging nations worldwide have had to pay for borrowing.

Since 2020, more than 60% of all rating actions have been classified as negative. “In 2024, 70% of the results were positive,” stated Grehan, who also mentioned that Aviva’s internal scoring models exhibited similarities.

Decade of downgrades

However, it is important to acknowledge that the ongoing series of enhancements will not fully compensate for the shortcomings of the past 10-15 years.

During that period, Turkey, South Africa, Brazil, and Russia all had their highly desired investment grade ratings downgraded. Additionally, there has been a significant increase in debt across most emerging markets, with the exception of the Gulf region, resulting in a decrease of more than one level in the average credit rating for emerging markets.

While some countries contend that rating agencies are showing more leniency towards industrialized economies with increasing debt, the financial situation of emerging markets is currently far from impressive.

Eldar Vakhitov, an independent analyst and “bond vigilante” at M&G Investments, highlights the International Monetary Fund’s recent projection that the average fiscal deficit of emerging markets will increase to 5.5% of GDP in the current year.

Merely twelve months ago, it was believed that the 2023 EM fiscal expansion was a singular occurrence that would be completely reversed in the current year. According to the prediction by the Fund, the budget deficit of the EM is projected to be above 5% of GDP until 2029.

What is the reason behind the increase in ratings?

“The starting point is crucial for certain countries,” Vakhitov stated, elucidating that while government deficits remained significant, they had decreased from their highest levels during the COVID pandemic.

Several nations, including Zambia, are experiencing a significant boost as they emerge from debt restructurings, while other regions are implementing noticeable policy enhancements.

Market pricing indicates that Turkey, which has implemented several measures to address its inflation issue, and Egypt, which has alleviated concerns about default, are both likely to receive significant upgrades.

“Rating agencies have a tendency to be sluggish,” Vakhitov remarked, “thus, it frequently requires a significant amount of time for them to provide upgrades.”

Payment of coupons.

The downgrades have not ceased entirely. China has received warnings from both Moody’s and Fitch in the past six months. Israel’s war has resulted in its first-ever downgrades, while Panama has lost one of its investment ratings.

Three years after the extravagant spending during the COVID pandemic, the expenses are now being settled. According to JP Morgan forecasts, the amortizations and coupon payments for EM hard currency debt are projected to reach a record-breaking amount of $134 billion this year.

The current figure represents an increase of $32 billion compared to the previous year. Therefore, it is understandable that policymakers in developing markets are highly motivated to take all possible measures to improve their ratings and maintain low borrowing rates.

In London this month, Indonesia’s Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati elucidated how the agencies expressed skepticism when she informed them during the COVID pandemic that Indonesia would successfully reduce its deficit to less than 3% of GDP over a span of 3 years.

“We were able to consolidate the fiscal position within a span of just two years,” she stated. “I consistently remind my rating agency staff that since I successfully won the bet, they are obligated to improve my rating.”

All Categories

Recent Posts

Tags

+13162306000

zoneyetu@yahoo.com